Combustion, Emissions and Toxicological Studies

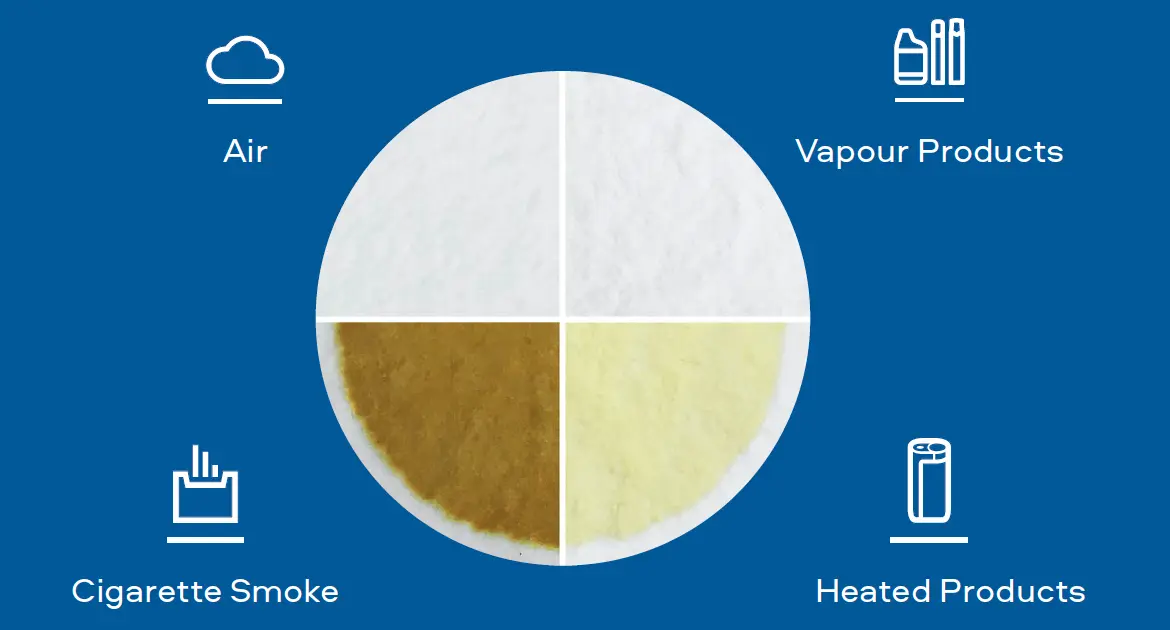

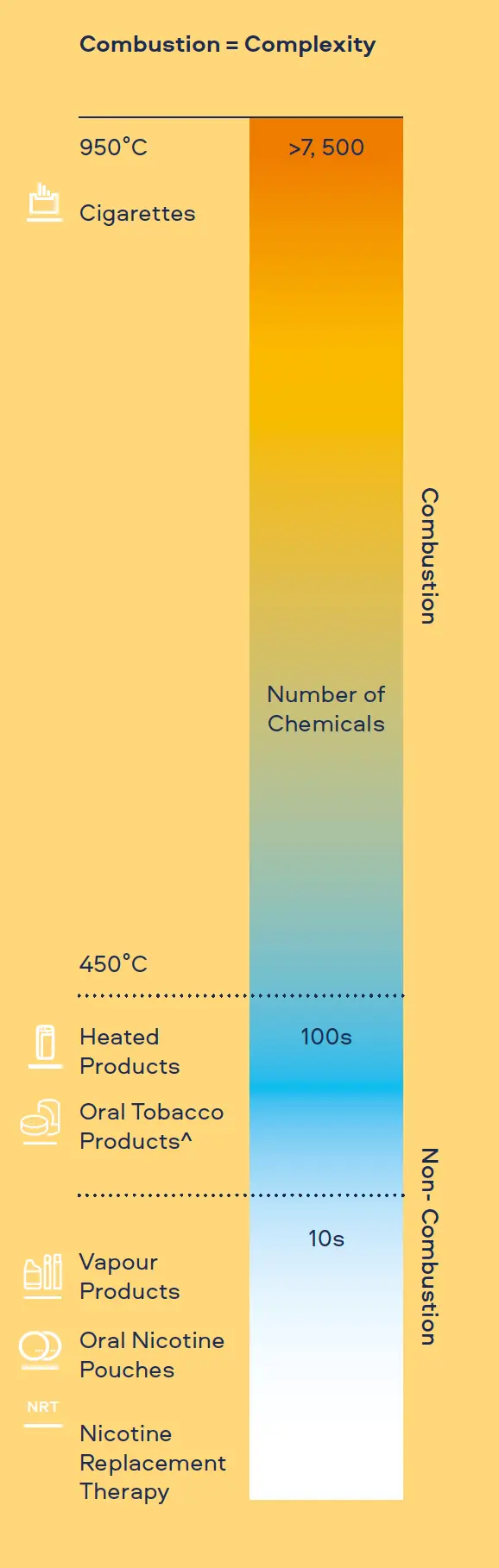

Cigarette smoke is an extremely complex and hazardous aerosol. It contains more than 7,500 individual chemicals, of which 150 are known to be harmful and more than 60 are known carcinogens.[1,2,3]

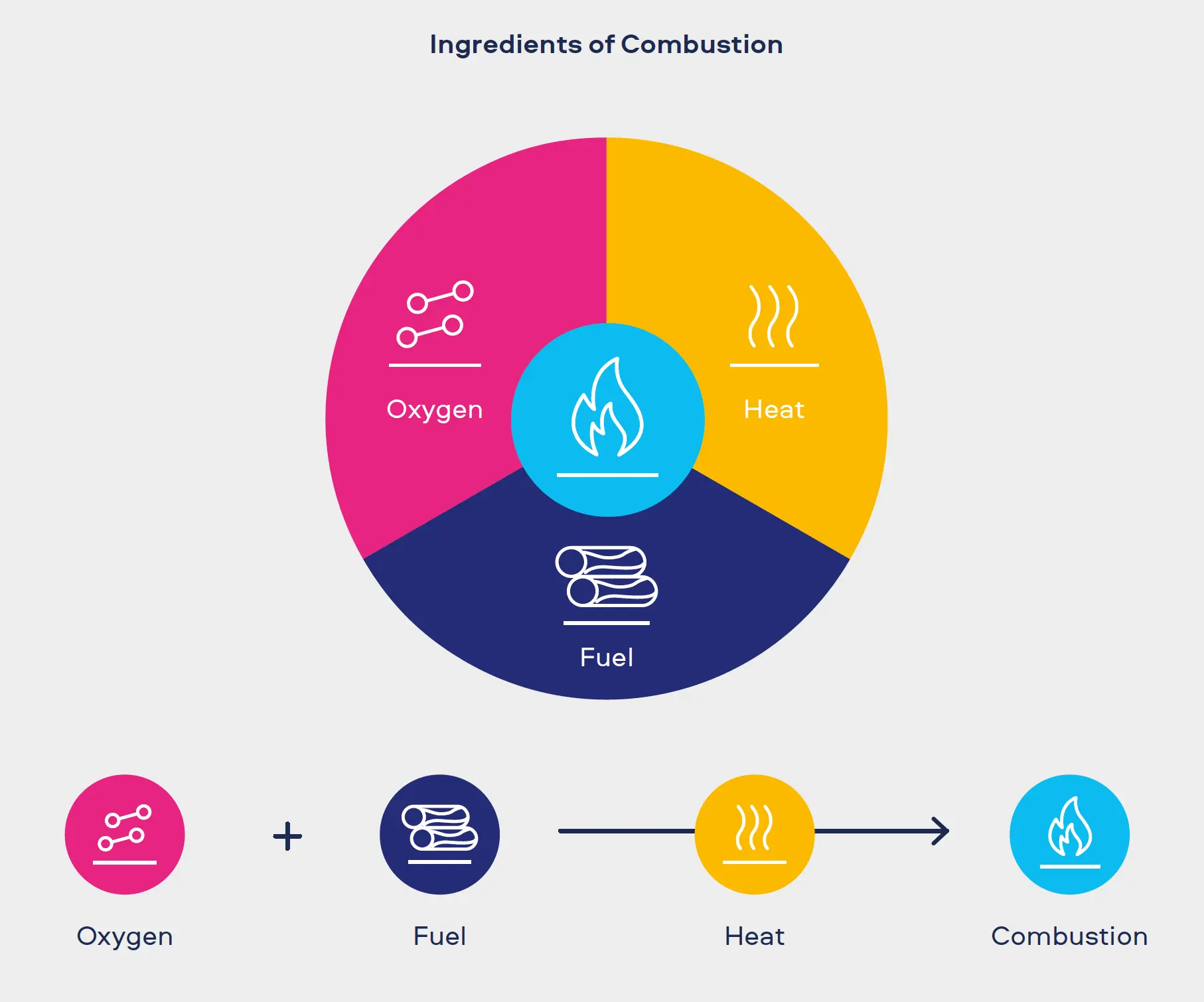

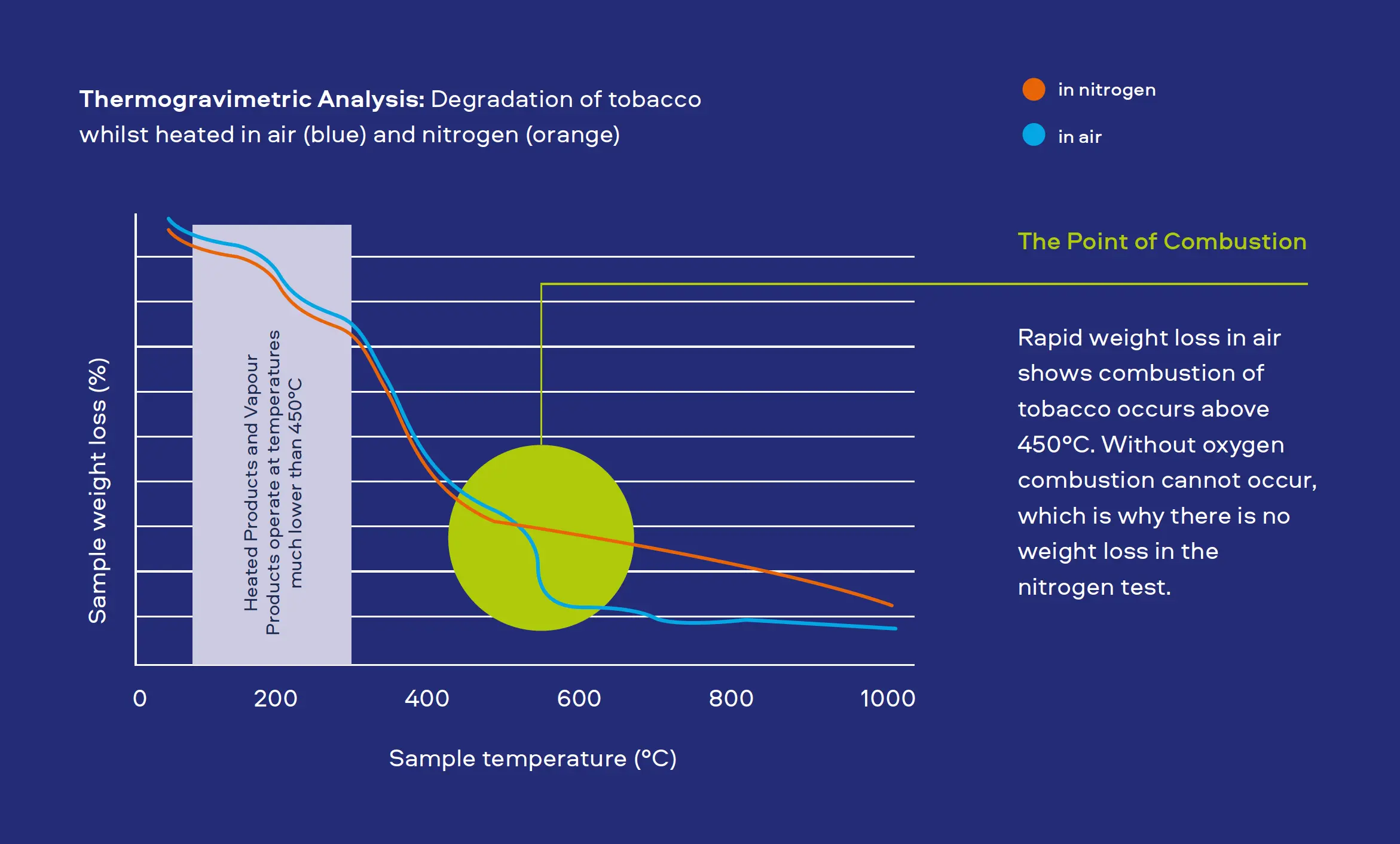

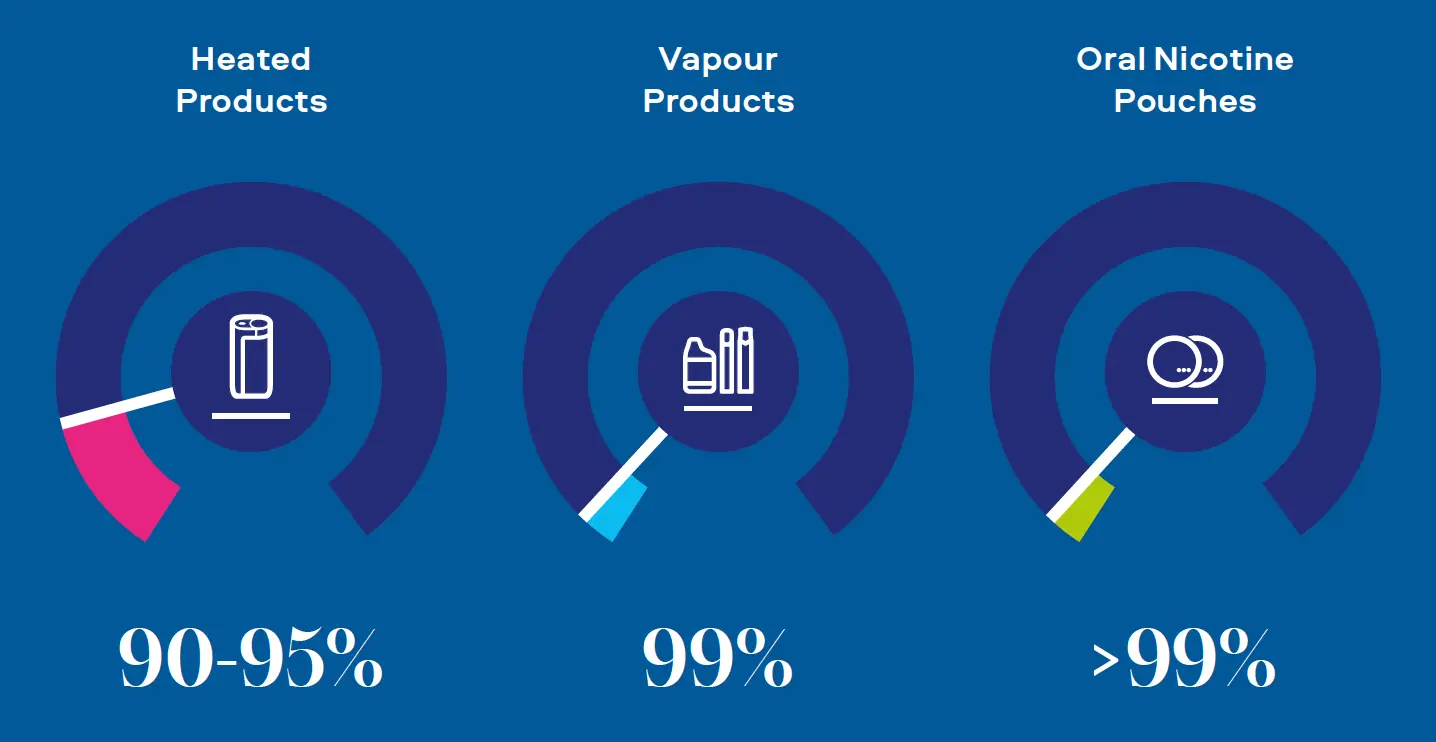

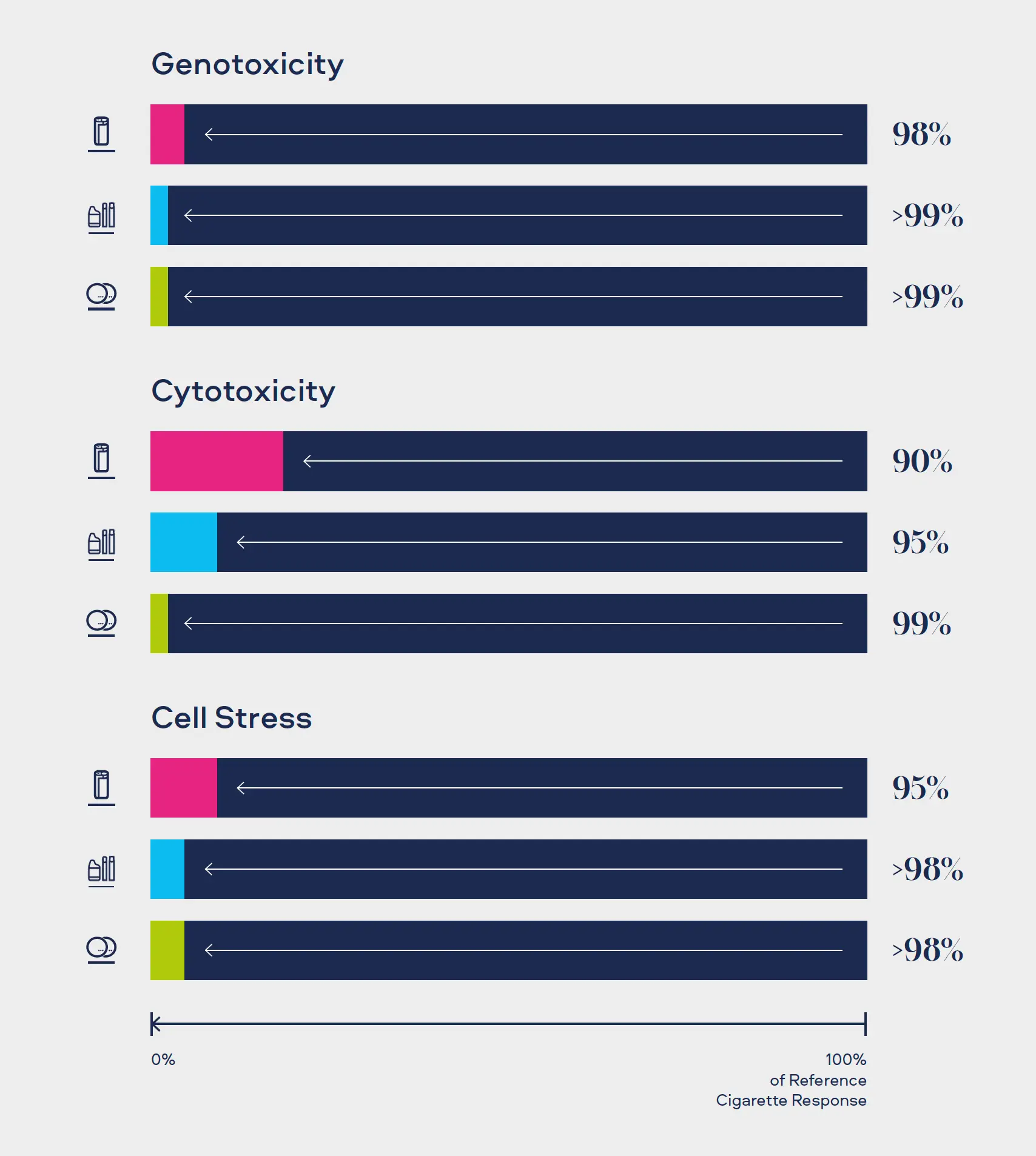

"Combustion equals complexity. Our Smokeless Products are shown not to combust. Without combustion our Smokeless Products have fewer chemicals present in their aerosols/extractions. The chemicals that are present are often greatly reduced compared to those found in cigarette smoke. Laboratory toxicological assessments further demonstrates that the reduction in chemicals result in little or no cytotoxicity, mutagenicity and genotoxicity compared with cigarette smoke."

Dr Marianna Gaca

Head of Global Analytical and Preclinical Research, Global Life Sciences